In the time it takes for a user to push a button or type a key, millions of clocks cycles may pass. Usually the user’s intention is to trigger a single event, not millions of them. To make things more complicated, buttons and keys tend to “bounce” when switching between 0 and 1. Instead of a clean transition, the signal may flutter back and forth before settling into a clear logic level. So a good Human Interface Device (HID) should reject the bouncing and reduce a long keypress to a single clean pulse lasting one clock cycle.

The debouncing problem also introduces the concept of asynchronous interfaces. A human user is not synchronized to the digital system’s clock, so the system needs to do some work to detect the information. The same problem occurs whenever signals needs to be exchanged between different digital systems that are on separate clocks. Such systems are not synchronized, hence they are called asynchronous.

The simplest debouncing strategy is to make a register assignment, like this:

module debouncer

(

input clk,

input btn,

output reg btn_db // debounced output

);

always @(posedge clk) begin

btn_db <= btn;

end

endmoduleThis always code is

sensitive to posedge clk,

so the value of btn is evaluated

only at the rising edge of the clock. That should take care of any

“fast” bouncing. Slower bouncing can be resolved using a clock divider

to make the assignments less frequent.

This method doesn’t resolve the long button press problem. What we really want is to trigger a single clock cycle pulse regardless of how long the button is held down. One way to do this is by adding delay registers as in the code below.

module debouncer

(

input clk,

input btn,

output reg btn_db // debounced output

);

reg btn_d; // button delay by one clock cycle

always @(posedge clk) begin

btn_d <= btn;

btn_db <= btn & ~btn_d; // true only when btn rises from 0 to 1

end

endmoduleHere there are two concurrent non-blocking

assignments. These assignments take effect in the next (future)

clock cycle. That means the btn_db assignment compares the value

of btn now to its value in the

previous cycle. The btn_db

output is only 1 for a single

clock cycle, when btn changes

from 0

to 1.

This style of debouncer is a good start, but still misses a bounce from time to time, resulting in unintended double-press errors.

A more robust debouncing approach is to ensure that the btn signal is 1 continuously

for some number of clock cycles, and then settles to zero for a number

of cycles. A standard way to count clock cycles is to use an alarm

timer. An example is given in src/tcounter.v,

listed here:

module tcounter

#(

parameter N=100

)

(

input clk,

input rst_l,

input clear,

output reg done

);

integer clk_count;

always @(posedge clk, negedge rst_l) begin

if (!rst_l) begin

done <= 0;

clk_count <= 0;

end

else begin

if (clear) begin

clk_count <= 0;

done <= 0;

end

else if (clk_count == N)

done <= 1;

else

clk_count <= clk_count + 1;

end

end

endmodule // tcounterIn this module, the alarm is reset when clear is 1. When clear drops from 1 to 0, the timer

starts counting. Once N clock

cycles have elapsed, done rises

from 0

to 1 and

stays high until another clear

signal is given.

Using this alarm timer, we can design a debouncer state machine with three states:

Let’s analyze the behavior in each of these states:

btn event. There are two outgoing

transitions:

clear is held at 1 so the tcounter is prepped.btn goes to

1, the

machine goes to state 1 and lowers

clear to start the alarm

counter.btn has gone to 1, and clear is 0 so the tcounter is running. There are three

outgoing transitions:

btn is 1, it waits

for the alarm t to

complete.btn “bounces” (i.e. goes back to 0) before the

alarm signal t, then the machine

resets to state 0.btn was stable at 1 until the

alarm t, then the machine is

allowed to proceed to state 2 when btn falls to 0. During this

transition, the output btn_db is

set to 1, and clear is set to 1 to reset the

tcounter.btn_db is set to 0 so that the

output pulse lasts a single clock cycle. There are two outgoing

transitions:

clear to 0 to start the

alarm timer. This creates a delay to allow any release bouncing to

settle.t is 1, the machine

returns to its initial state. The condition is t & !clear

since both t and clear are 1 upon exiting

state 1 (it takes an extra clock cycle for the tcounter to reset itself).localparam for

Descriptive State NamesNumerical state values can be confusing when analyzing a complex or

high-level FSM. Many designers prefer to use Verilog constants with

local scope (i.e. defined only within the module). This is done using

the localparam

syntax.

Instead of using states 0, 1 and 2, we give

them names:

localparam WAIT = 0;

localparam PRESS = 1;

localparam RELEASE = 2;Later in the code, these names can be used as if they were numerical constants.

Create a file named src/debouncer.v

and declare a module named debouncer. Use the code fragment shown

below as a template. The first state is already done.

module debouncer

(

input clk,

input rst_l,

input btn,

output reg btn_db

);

reg [1:0] state;

reg clear;

wire t; // tcounter timer alarm

localparam WAIT = 0;

localparam PRESS = 1;

localparam RELEASE = 2;

// tcounter instance

tcounter T1

(

.clk(clk),

.rst_l(rst_l),

.clear(clear),

.done(t)

);

initial begin

state = WAIT;

clear = 1;

btn_db = 0;

end

always @(posedge clk, negedge rst_l) begin

if (!rst_l) begin

state <= WAIT;

clear <= 1;

btn_db <= 0;

end

else begin

case (state)

WAIT:

begin

// btn_db is set to zero for all transitions

// from this state

btn_db <= 0;

if (btn) begin

state <= PRESS; // change state

clear <= 0; // start the timer

end

else

clear <= 1;

end

PRESS:

begin

// YOU DO THIS

end

RELEASE:

begin

// YOU DO THIS

end

default:

// DEFAULT behavior is necessary since we aren't

// using state 2'b11 ('d3). If the module somehow

// arrives in state 3, we need to give it a way

// back to normal functioning so it can recover

// gracefully from faults.

begin

btn_db <= 0;

clear <= 1;

state <= WAIT;

end

endcase

end

end

endmodule // debouncertop ModuleWe will use a top-level wrapper module to do the following:

debouncerrst

button to active-low rst_l

signalbtn_db and use it to

toggle an LED outputmodule top

(

input clk,

input btn,

input rst,

output reg led

);

wire btn_db;

wire rst_l;

assign rst_l = ~rst;

initial begin

led = 0;

end

debouncer db1

(

.clk(clk),

.rst_l(rst_l),

.btn(btn),

.btn_db(btn_db)

);

always @(posedge clk, negedge rst_l) begin

if (!rst_l) begin

led <= 0;

end

// Toggle the LED if the button is pressed:

else begin

if (btn_db)

led <= ~led;

end

end

endmodule // topOpen src/testbench.v

and find the lines below. These create a stimulus pattern to simulate a

bouncing button press. The btn

signal bounces from 0 to 1 starting at

cycle 10, then remains stable at 1 until cycle

200, then bounces back to 0 until it

becomes stable again at cycle 235:

case (clk_count)

10: // start button press

btn <= 1;

20: // bounce

btn <= 0;

24: //bounce

btn <= 1;

30: //bounce

btn <= 0;

31: // now sustain

btn <= 1;

200: // release

btn <= 0;

210: // bounce

btn <= 1;

215: // bounce

btn <= 0;

230: //bounce

btn <= 1;

235: //sustain

btn <= 0;

endcase // case (clk_count)The simulation is run until 500 clock cycles in order to verify that the state returns to zero after the button stabilizes:

// DEFINE WHEN TO TERMINATE SIMULATION:

always @(posedge clk) begin

clk_count <= clk_count + 1;

if (clk_count == 500) begin

$fclose(fid);

$finish;

end

endRun the simulation using make

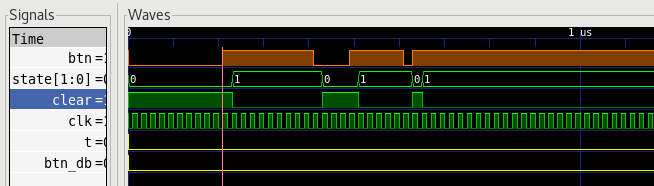

and you should see output like this:

clk: 11 clk diff: 11 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 12 clk diff: 1 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 21 clk diff: 9 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 0

clk: 22 clk diff: 1 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 0

clk: 25 clk diff: 3 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 26 clk diff: 1 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 31 clk diff: 5 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 0

clk: 32 clk diff: 1 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 33 clk diff: 1 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 134 clk diff: 101 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 1 btn: 1 led: 0

clk: 201 clk diff: 67 state: 1 clear: 0 t: 1 btn: 0 led: 0

clk: 202 clk diff: 1 state: 2 clear: 1 t: 1 btn: 0 led: 0

clk: 203 clk diff: 1 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 1

clk: 211 clk diff: 8 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 1

clk: 216 clk diff: 5 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 1

clk: 231 clk diff: 15 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 1 led: 1

clk: 236 clk diff: 5 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 1

clk: 304 clk diff: 68 state: 2 clear: 0 t: 1 btn: 0 led: 1

clk: 305 clk diff: 1 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 1 btn: 0 led: 1

clk: 306 clk diff: 1 state: 0 clear: 1 t: 0 btn: 0 led: 1The output lines are only printed when there is an

interesting signal change (see explanation in the next

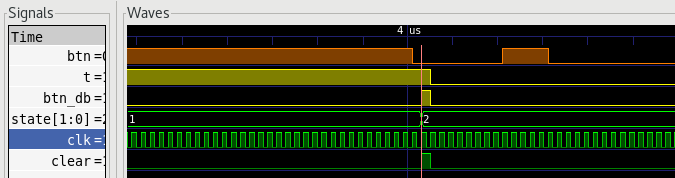

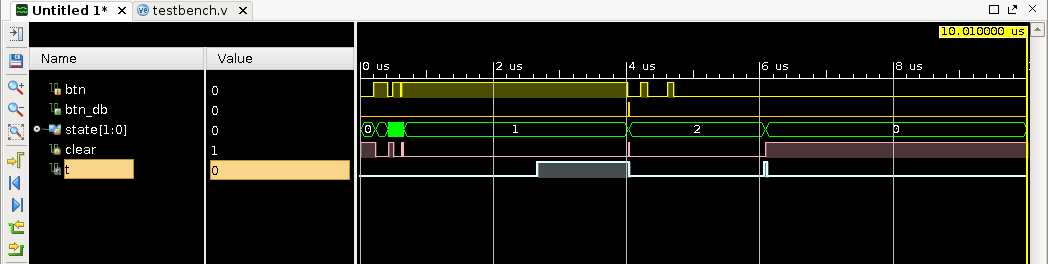

section). In the first line of output at clock 11, we see btn go high, then the FSM state goes

to state 1 at clock 12. The btn

bounces a few times causing state to cycle between 0 and 1.

The btn signal stabilizes at

clock 33, and the alarm t is

finished at clock 134. At this point the FSM sits in state 1 until btn goes low at clock 201. At this

point the FSM transitions to state 2, and btn_db is pulsed causing led to toggle.

The FSM then loiters in state 2 until clock 304 when t fires again. At clock 305 the btn has stabilized, and the FSM is

back in state 0, ready to detect a new button press.

In this project we explore several new options for data visualization. Instead of straining over a raw cycle-by-cycle text dump, we can use several methods to make the data more interpretable.

To make the text output readable, we only print an output line when an interesting change occurs. To detect these changes, we use a set of delay registers and use XOR operations to detect when something has gone from 0-to-1 or 1-to-0:

reg btn_d; // delayed button (to detect changes)

reg led_d; // delayed led

reg state_d; // delayed debouncer state

reg clear_d; // delayed clear signal

reg t_d; // delayed timer alarm

reg value_change; // 1 if something changes, 0 otherwise

always @(*) begin

value_change = btn ^ btn_d;

value_change = value_change | (led ^ led_d);

value_change = value_change | (DUT.db1.clear ^ clear_d);

value_change = value_change | (DUT.db1.state ^ state_d);

value_change = value_change | (DUT.db1.t ^ t_d);

end

always @(posedge clk) begin

// print data summary only if there is a change:

if (value_change) begin

clk_count_d <= clk_count;

$write("clk: %4d", clk_count);

$write(" clk diff: %4d", clk_count-clk_count_d);

$write(" state: %1d", DUT.db1.state);

$write(" clear: %b", DUT.db1.clear);

// ... and so on ... //

end

endThese lines produce a tab delimited data file in

test_result.txt:

$fwrite(fid,"%4d", clk_count);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%4d", clk_count-clk_count_d);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%1d", DUT.db1.state);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%b", DUT.db1.clear);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%b", DUT.db1.t);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%b", btn);

$fwrite(fid,"\t%d", led);

$fwrite(fid,"\n");A tab-delimited file can be imported by many software applications.

In Matlab, you can use the importdata command:

d = importdata('test_result.txt');The data is loaded into a matrix named d. You can plot columns from the data

using the plot, stem, or stairs commands, for example:

stairs(d(:,1),d(:,6))

xlabel('Clock Cycle')

ylabel('btn')xsim in GUI modeThe Vivado graphical interface can be used by running the simulation in GUI mode:

make guiThis allows using the graphical interface to zoom and view signals side-by-side:

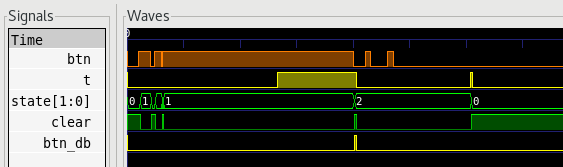

gtkwave to view vcd fileThese lines in src/testbench.v

direct the simulator to create a Value Change Dump

(VCD) file for the indicated module. VCD files are used to

exchange simulation data between a variety of analysis tools.

// INITIAL SIGNAL CONFIGURATION:

initial begin

$dumpfile("debounce.vcd");

$dumpvars(1,DUT.db1);

endThe simulator will save all the signal changes in the db1 module and dump them into debounce.vcd. There are a number of

lightweight programs for viewing VCD files. One of the more popular

tools is gtkwave, which is a

multi-platform free option.

Copy the master XDC file, Basys3_Master.xdc to a new one named

debouncer.xdc. In debouncer.xdc, locate all the lines

corresponding to these ports, and move them to the top of the file:

clkbtnC – rename to rstbtnU – rename to btnLED[0]

– rename to ledThen delete all the other lines since we aren’t using any other resources.

Run make implement to build

your design, and program it onto the Basys3 board. Record a short video

showing yourself pressing the button a few times. The LED should toggle

ON/OFF each time you press and release the button.

Turn in your work using git:

git add src/*.v *.v *.rpt *.txt *.tcl *.bit *.xdc

git commit . -m "Complete"

git push origin mainUpload your video on Canvas to indicate that your assignment is done.